It is commonly thought that more nuance is always a positive thing. Very rarely do you hear someone say, “We should be less nuanced about this.” But is nuance always useful? And what even is nuance, anyway?

Imagine you are looking at the beautiful skyline of downtown Dallas. You see some of Dallas’s iconic buildings, including the Reunion Tower. A bunch of different structures inhabit your field of vision. What kinds of questions would it make sense for you to ask about what you see? You could potentially ask about how many buildings are open for business, what the crime rates are in the area, what parts of downtown are prone to traffic, where the construction zones are, etc. Let’s say that, while you’re looking at downtown Dallas, you ask, “Where are the best parking lots?”

Now, imagine you focus your attention on just the Reunion Tower. By zooming-in your visual scope, you have transitioned from looking at the more general downtown Dallas to the more specific Reunion Tower. What kind of questions would it make sense for you to ask about what you see at this point? You could potentially ask about how tall the tower is, the prices at the restaurant, how many people work there, etc. Pretend that, while you’re looking at the Reunion Tower, you ask, “What is the dinner menu at the restaurant?“

I think we can agree that, if you swapped the questions in these two instances, they would both makes less sense to ask. If you were looking at the downtown Dallas skyline with your friend and ask them “What is the dinner menu at the restaurant?“ they would likely respond by asking “Which restaurant?” And if you were looking just at the Reunion Tower with your friend and you asked them “Where are the best parking lots?” they would probably give you a confused look and say “There are no parking lots in the Reunion Tower.”

Your friend’s answers would be predictable. It makes sense that they would respond these ways to your questions about what you’re looking at in both cases. Their answers would be as sensible as your questions insensible. But why would their responses make sense? And why would your questions not make sense?

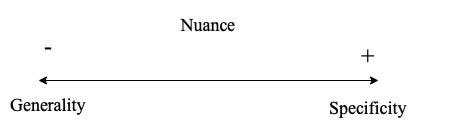

Enter: The interrelated concepts of nuance, generality, and specificity. The term “nuance“ refers to the amount of generality or specificity exhibited by a frame of analysis (e.g., downtown Dallas, Reunion Tower). Generality and specificity are situated on opposite sides of the nuance continuum. They are inversely related concepts. More generality means less specificity, and vice versa. When we say that something is “more nuanced” than something else, we mean that it is more conceptually specific.

Generality and specificity are also relative concepts (indexicals). There is no such thing as absolute generality or specificity. We can only identify how general or specific a frame is by comparing it to another frame. An analytical frame containing the entire skyline of downtown Dallas is more general, or less specific, than an analytical frame containing only the Reunion Tower. We know this because the downtown Dallas frame includes everything that is in the Reunion Tower frame and more. When one frame subsumes another, the subsumed frame is considered more specific.

Injecting nuance only makes sense when it increases parsimony. Parsimony is a measure of a linguistic project’s efficiency. Linguistic projects are endeavors that use language to accomplish a specified or unspecified goal or set of goals (e.g., conversations, essays, presentations, billboards, poems). A parsimonious linguistic project is one that fulfills its goal(s) quickly and completely. This means that its content, on the whole, balances substance and speed in a goal-fulfilling way.

Parsimony isn’t equivocal to brevity because many linguistic projects concern complicated topics that take time to adequately articulate. It’s often hard to strike a goal-fulfilling balance between substance and speed because it isn’t always clear which details are useful to include.

Nuance contributes to or detracts from parsimony by modifying analytical frames. To add nuance is to shrink the scope of a linguistic project by making its frame more specific.

When we put these strands together, we get the following: Nuance is only useful when shrinking the frame of a linguistic project establishes a more goal-fulfilling balance between substance and speed.

To argue that more nuance is always good is to argue that more conceptual specificity is always useful in conversations. However, as the example of the two Dallas frames shows, this is clearly not true. If the operative analytical frame in a conversation shrinks from the more general Dallas skyline to the more specific Reunion Tower, certain kinds of questions become nonsensical to ask or more difficult to address. If you ask “Where are the best parking lots?“ in a conversation about the Reunion Tower, everyone would need to first expand the conversational frame to contain all of downtown Dallas before addressing your question. In this case, it would be more useful to decrease the frame’s nuance. In other words, it would be more useful to increase the frame’s generality (or decrease its specificity).

When thinking about whether more nuance would be beneficial, it’s useful to think in terms of visual zooming: Would it be better to zoom-in on a particular element in the frame? The answer depends on the conversation’s goal.

The next time someone suggests more nuance, consider asking them why. One way to do this is to inquire “What thing should we be looking at to best accomplish our goal here?” or “What idea should we be thinking about to best accomplish our goal here?”

A lot of the time, people suggest more nuance because they don’t have anything actually useful to contribute. Not all nuance is beneficial because not all nuance contributes parsimony. Sometimes it’s much more useful to zoom out.