Laughing is one of those things we (hopefully) do a lot without really understanding why. When someone misses the joke and we explain it to them, they may "get it now" but they rarely "get it" in the spontaneous, organic way we did. Their understanding of it is detached and abstract, not felt. What explains the comedic reaction? And what predicts whether a joke will evoke visceral outrage rather than laugher? I offer a theory which suggests that whether, what, and when something is funny is a function of the nature of the sociomoral conditions in which a joke is delivered and the jokester's manipulation of those conditions.

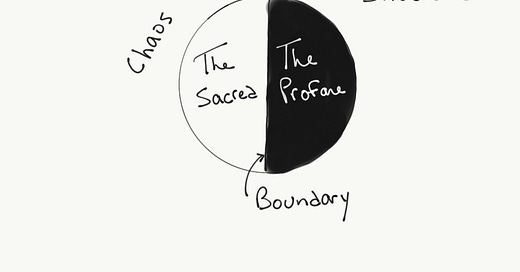

These conditions can be conceptualized in terms of moral boundaries and moral boundary structures. Each boundary segregates the sacred from the profane along some socially salient dimension. Together these boundaries distinguish within a moral community the polite from the rude, the righteous from the heretical, the socially just from the oppressive, and so on. Moral boundary structures, moralities or moral systems comprised of sacred values and guiding ethical principles, produce these boundaries. These systems make things make sense, they provide interpretive frameworks through which we - typically effortlessly and automatically - categorize elements of our experience as good or bad.

Boundary Subversion: Comedic Relief

Many jokes are funny because they momentarily subvert moral boundaries felt to exist by the audience. In other words, they temporarily invert the sacred and profane in a manner which exposes a contradiction or tension of some kind. The comedic relief a successful joke of this sort elicits results from the brief relaxation of a moral constraint and the glee which accompanies this loosening of stricture. A joke by comedian Louis C.K. about his desire to trade his first class airline seat with a soldier sitting coach illustrates this dynamic well:

Every time I see a soldier on a plane I always think, 'You know what? I should give him my seat.' It would be the right thing to do, it would be easy to do, and it would mean a lot to him. I could go up to him, 'Hey son' - I get to call him son - 'go ahead and take my seat.' Because I'm in first class why? For being a professional asshole. ... This guy is giving his life for the country... ... He's told by everyone in his life system that's a great thing to do and he's doing it! And it's scary, but he's doing it and he's sitting in this shitty seat. And I should trade with him. I never have. Let me make that clear. I've never done it once. And I've had so many opportunities. I never even really seriously came close. And here's the worst part. I still enjoyed the fantasy for myself to enjoy. I was actually proud of myself for having thought of it! I was proud!

C.K. subverts the moral boundary designating appropriate feelings towards American soldiers - respect, appreciation, admiration - by juxtaposing his recognition of it with his failure to fulfill its implications. We can relate to the conflict. We see what this sort of boundary means in situations of this sort yet we feel the selfish resistance. C.K.'s admission is shameful, but the delivery of it in a comedic context allows for the temporary suspense of the feeling of shame. The audience gets the opportunity to subvert a moral boundary with the comedian in spirit and relish the pseudo-rebellion. Boundary subversion is permitted in the comedic context because of the mutual recognition that the moral inversion is temporary and simulated. Once the context changes, the boundary and the felt shame its trespass delivers returns in full.

Boundary Dissolution: Absurdity Embrace

If the moral boundary structure collapses, the orientating interpretive framework we unconsciously employ to categorize experience implodes leaving us without the ability to discriminate between funny and not funny. The order once established gives way to chaos and anomie (moral disregulation). No character embodies the nihilistic urge to destroy boundary structures and embrace the chaos they stave off like the Joker. In the latest cinematic rendition of the Joker with Joaquin Phoenix, he has this exchange with talk show host Murray Franklin following his public confession of murder:

Murray: You think that killing those guys is funny?

Joker: I do and I'm tired of pretending it's not. Comedy is subjective, Murray. Isn't that what they say? All of you, the system that knows so much. You decide what's right or wrong the same way that you decide what's funny or not. ... I killed those guys because they were awful. Everybody is awful these days. It's enough to make anyone crazy.

Murray: Okay, so that's it. You're crazy? That's your defense for killing three young men?

Joker (in comedic tone): No...they couldn't carry a tune to save their lives!

(Joker smiles as the crowd boos)

Joker is not subverting a moral boundary because he is not exposing a tension or juxtaposing the sacred with the profane in socially discouraged manner to illustrate a contradiction. Instead, he is attacking the value of human life underlying the moral boundary structure to which the audience subscribes. His comedy is thus one of profound negation. In a similar act, Heath Ledger's Joker sets fire to a mountain of cash in The Dark Knight. Rather than subverting the market principles of the economic boundary structure by, say, paying too much for too little or vice versa, Joker negates a foundational assumption of the system. He revokes the value of money itself. In the absurd scenario, nihilistic chaos reigns and anything can be funny for that which once limited the scope of the funny is no longer in place.

Boundary Protection: Deconstruction Threat

When those emotionally connected to a boundary structure believe the structure is precarious, they respond to the subversion of its boundaries with negative sanctions in an effort to protect the structure from collapse. Subversion of sturdy boundaries poses little to no risk of deconstruction because both the audience members and the comedian are confident that they will still feel the boundary's existence when the comedic context dissipates. Louis C.K. can joke about failing to actively honor an American soldier because it is obvious to everyone in the theater that American soldiers deserve honor. If the simulated subversion of this value had the high potential of undermining its existence, C.K.'s joke would be received with outrage not laugher.

The desire to strengthen a boundary structure by punishing those who subvert its boundaries in any context explains the phenomena of the hyper-online "progressive" woke-scolding of comedians, satirists, and jokesters and the prudish right-wing pearl clutching condemnation of irreverent humor. In actuality, the reactions of these groups are two manifestations of the same impulse: In order to support the social proliferation of our unpopular morality, we must protect its values and principles against permanent subversion by punishing anyone who trespasses the structure's moral boundaries without feeling properly ashamed. The fear is that the shameless simulation of boundary subversion threatens the actual integrity of the boundary in simulators' psyches. What if the temporary subversion in the comedic context is not temporary at all? Maybe the joke will expose a fundamental weakness in the boundary structure and the moral system will become even less popular among social others than it already is! Maybe people won't feel the shame they deserve to feel for trespassing a boundary after they leave the comedy theater. Paradoxically, the impulse to punish the deviant smacks of its own shame, the shame of unpopularity ("If these likable people think what I believe is dumb, what does that say about me?").

Whether the coercive response resolves the deconstruction threat posed by comedic subversion, and whether such threat exists in the first place, are empirical questions. My sense is that the deconstruction threat is real. Satire's power derives from its ability to influence how people think and feel about the sacred and the profane in the real world. I personally tend to respond to coercive shaming with indignation. My laughter becomes less of a gut response and more of a political/moral protestation of my individual agency that I pit against your sense of righteous possession. Your ideas cannot control me. Whether this reaction is normative, I do not know.