Social theorist George Herbert Mead distinguishes between two aspects of the self. “The self is both the ‘I’ and the ‘me;’ the ‘me’ setting the situation to which the ‘I’ responds. … The relationship of the ‘me’ to the ‘I’ is the relationship of a situation to the organism.”

In a classic essay, Mead contrasts religious experience with teamwork to elaborate this distinction. A good soccer player knows from practice where his teammates are on the field and how they will respond to changes in the game. When the other team makes a play, the player predicts how his teammates will respond in order to determine what he should do. This information about the social situation is held in the “me,” it tells the player “This is what is left for me to do.” The player’s “I” acts upon the information in the “me” by, for instance, running to a certain spot on the field in order to receive a pass.

Teamwork requires that members differentiate themselves from the rest of the team in order to achieve their group’s objective. The “me” continuously updates information about other members’ activity so that the “I” can respond to the changing social situation and perform its function in the group project. If each member does this well, then the whole team’s actions are harmonized, and the team acts in unity.

In certain religious contexts, there is a “fusion of the ‘I’ and the ‘me,’ which leads to intense emotional experiences.” Unlike in teamwork where the “I” responds to a social “me” that individuates functions for each member, religious experience involves a complete identification with the group. Everyone is one, the same, functionally undifferentiated.

Take the experience of someone “losing herself” in a religious ritual like singing a worship song. Her “I” isn’t responding functionally. She’s not processing “Pam is doing this and Alyona is doing that” and concluding “This is what is left for me to do.” Instead, her “me” and “I” fuse. Everyone is performing the same function. Since there isn’t a functional differentiation among people, there isn’t a psychological separation of the “me” and the “I.” Mead writes that patriotic experiences, such as singing the anthem, involve the same social psychological dynamics.

Mead’s theory rejects the Cartesian cogito “I think, therefore I am.” In teamwork contexts, thinking and being are functionally differentiated. In the religious situation, thinking and being are fused together. Since you think differently in different social environments, you exist differently — being a part of a group versus being unified with everyone.

The distinction between the “me” and the “I” is often absent in discussions of “self-actualization.” People talk about “finding themselves” through activities that relate the “me” to the “I” in fundamentally different ways. An athlete finds himself in his differentiated role on the field, a believer in her unified identification with the congregation. There aren’t just various ways to actualize a self but multiple types of actualizable selfhood — multiple possible kinds of relationships between the “I” and the “me.” A critical question arises for the “self-actualized” person: What kind of self have you actualized?

The question exposes the fatalism of claims to self-actualization by invoking multiple possibilities, disturbing the underlying assumption of a singular individual destiny. The self isn’t a pre-existing thing that is actualized over time, but a social psychological relationship formed through choices about which social environments to inhabit and how to participate in them.

Today, this fatalism is commonly expressed in terms of identity. Identity is thought to be revealed and not decided. This perspective subordinates the “I” to the “me” by privileging the formative power of social classification over that of individual action. You are a member of the team of society and need only marshal information about society’s expectations of your role in order to become who you already are. Identity is destiny.

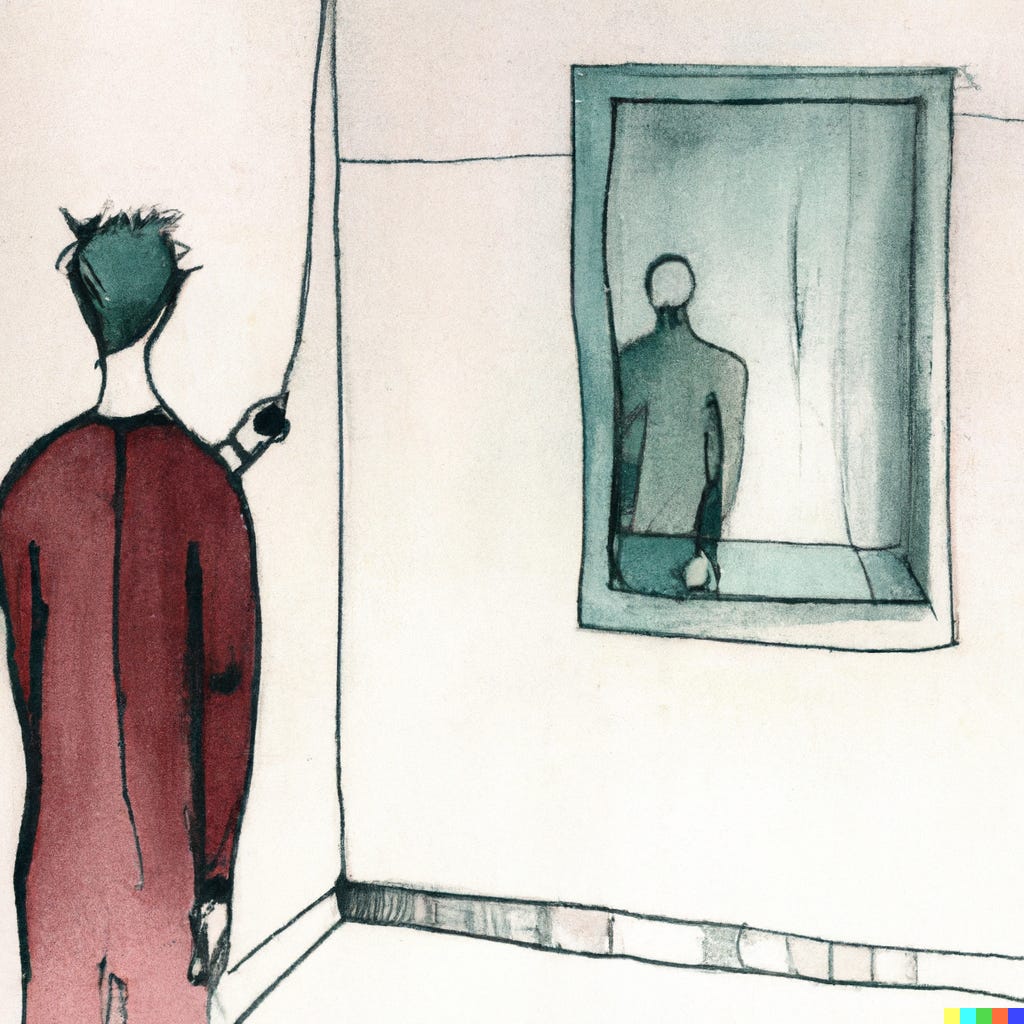

This explains why a person would make the peculiar claim that a classification must be socially recognized for her to “exist” and argue that objecting to the classification means denying her existence. This passive kind of self is only visible in a social mirror, a “me” without an “I.”

Mead’s theory does not allow for complete freedom. Since people are socialized from birth, information about social expectations and classifications will always feed into personal life choices. However, it specifies an opportunity for a balanced relationship. The “I,” what one chooses to do, can relate to the “me,” one’s understanding of the social environment, in a way that is not oppressive. One can start a new team or a new church that doesn’t fit existing social classifications and form oneself within that yet socially uncategorized environment. The identity-as-destiny perspective on the other hand enslaves the actor to socially recognized classifications and thereby constrains selfhood’s potential. Since pre-existing social convention is required to justify being, this perspective takes an inherently conservative approach to selfhood.

People who frequently talk about the need to recognize and represent identity are typically labeled “progressive” under the American political typology. However, true progression in social classification begins with being that isn’t justified by old or new traditions. Progressive existential artists create new categories by actually living lives that go beyond and deny the need for existing social classifications. The categories come later, if ever, and are usually invented by others to help them understand this new lifestyle.

Creating a tradition in order to be differs significantly from being in a way that creates a tradition. The former may seem progressive on its face because it introduces new terminology, but it takes a deeply conservative approach to life. Conservatives limit the “I” by requiring that it fit with socially recognized traditions. It is not the progressive but the conservative who freezes when their being exceeds social classification and requires that a new tradition be formed to justify their actions and “validate their existence.”