The Need for Psycho-Theologies

A Theology

A Psychology

A Psycho-Theology

Conclusion

The Need for Psycho-Theologies

They preach to the choir

Always in the permanent daylight

They toss paper tigers from their

Perfect porcelain skylines

Listen for the sound

As it all comes crashing down

The modern compartmentalization of theology and psychology has contributed to the decline in religiosity and the rise of mental illness. Religiosity and psychological health are mutually supportive, but we lack ways of discussing the relationship between these domains of life.

Fundamentalists are destroying their religions by conflating practical interpretations and applications with heresy and hypocrisy. They are taking their revenge on the scientific revolution by making their theologies as incompatible with modernity as possible. They extol physical death, demand scientific illiteracy, and then wonder why their religions are failing.

Theology without psychology is increasingly uninhabitable. It promotes increasingly negative concepts — not in this life, not of this dimension, not understandable with your human mind. If being religious means waiting to die and go to an unknown dimension to understand supposedly incomprehensible concepts, then religion is impractical for the living.

I do not think that is what religion truly is. Religion is a disciplined way of living. It should improve people’s lives over the long term and form healthy communities. It should be practical.

Theology without psychology fails to systematically address mental disorder. Although religious people generally recognize that mental illness and spiritual disconnection are somehow intertwined, they lack accessible ways of discussing how or why these things relate to one another. Many shy away from the ambiguity and opt to label all mental illness “immorality” or all immorality “mental illness.” These all-or-nothing approaches fall short.

Psychology without theology is also increasingly negative. The number of pathologies is growing while the diagnostic criteria are broadening. At this rate, everyone will soon be mentally ill in one way or another, and “mental illness” as a category will lose much of its practical utility.

Often, those who speak the language of mental health the best are the most unwell. They try to turn their psychological projects into religions, but psychology is predominantly a tool for overcoming disorder. It doesn’t do a good job of showing people what a well-ordered life is like or conveying a purpose for such a life.

Psychology without religiosity is also too individualistic to promote holistic health. It is too easy to weaponize psychological vocabularies against others for personal gain and against oneself to avoid responsibility. Without a complementary moral framework, psychology results in a lonely individualism that worships the half-baked idea of the un-disordered self.

We need psycho-theologies that integrate theological and psychological frameworks across world religions. Psychology can constrain the excesses of theology and vice versa. We know too much about mental illness, and we see too much spiritual aimlessness, to keep these domains separate any longer.

Below, I provide a rough illustration of what a psycho-theology could look like. It is by no means complete or exhaustive, but hopefully, it will express the idea.

A Theology

(14) And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, (15) that whoever believes in him may have eternal life. (16) For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life.

– John 3:14-16 ESV

John 3:16 is the most often quoted Bible verse. Verses 14-15 are far less popular even though they provide key context. When Christians quote 3:16, they implicitly convey the core message of their theology. The phrase “believes in him” encapsulates their view of the Christian way of life. Different denominations have different understandings of what it means to “believe in Jesus.”

In my church experience, discussions about 3:16 were rarely explicitly connected to Moses’s lifting of the serpent in the wilderness. This is a reference to a peculiar story in Numbers 21 involving “fiery serpents” sent by God that would bite the Israelites. Israelites who were bit would “die” unless they saw a pole Moses made with a bronze snake on it. This is supposed to explain how Christian belief should be, but what on earth does it mean to believe like that?

From Mount Hor they set out by the way to the Red Sea, to go around the land of Edom. And the people became impatient on the way. And the people spoke against God and against Moses, “Why have you brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness? For there is no food and no water, and we loathe this worthless food.”

Then the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people, so that many people of Israel died. And the people came to Moses and said, “We have sinned, for we have spoken against the Lord and against you. Pray to the Lord, that he take away the serpents from us.”

So Moses prayed for the people. And the Lord said to Moses, “Make a fiery serpent and set it on a pole, and everyone who is bitten, when he sees it, shall live.”

So Moses made a bronze serpent and set it on a pole. And if a serpent bit anyone, he would look at the bronze serpent and live.

– Numbers 21:4-9 ESV

I understand this story in an allegorical way. I don’t think it literally occurred. However, whether you understand it literally or symbolically has little, if any, practical significance. Even if I believed that there were actual snakes, I’d still recognize that the story’s application is necessarily metaphorical. John isn’t saying that believing in Jesus means looking at Moses’s bronze snake pole when you are bitten by a copperhead on a hike. That would be really stupid.

Instead, understanding the story’s relevance requires thinking by analogy. The “as, so” language in verse 14 clearly communicates this. As with this, so with that. Even if the events literally occurred, something about the way they unfolded tells us something about how Christian belief manifests according to John. John implores his readers to search for parallels between the story and their lives in order to understand verse 16.

The only way to find these convergences is to explore the possible symbolic meanings of the characters and plot in the story. What was the cultural significance of the snake to the Israelites? What are fiery snakes in my life? What does a life-saving snake pole represent? Through questions like these, we can find answers.

Ancient cultures independently developed profound symbolism around the snake. It’s one of the oldest and richest symbols. The snake grows and sheds skins, representing the complex dynamic between continuity and transformation. Like the snake, we change significantly while remaining in a sense fundamentally the same.

Phases of the snake’s life are marked by its skins. When a snake sheds its skin and grows a different one, it lives in a new way from before. A snakeskin represents a temporary existential and experiential stage. Our snakeskin is our understanding of and feelings throughout life as it is within our current chapter. Maybe we will die tomorrow and our stories will end, but there’s always at least the possibility of starting a new chapter in which we live a different kind of life and experience the world in a new way. We grow and shed skins, or transform through different ways of living.

Mose’s snake pole is similar in structure and meaning to the Rod of Asclepius in Greek mythology. Asclepius was a god of medicine and Moses’s pole healed the Israelites. The snake pole also closely resembles the Andry Tree, which depicts a tree snaking up a pole and is a prominent symbol among orthopedics. I first discovered the Andry Tree in Michel Foucault’s Discipline & Punish. All these symbols have to do with the healing power of correction. Something which is in a bad way can be “straightened out” through conformity with a structure aimed toward what is higher and better (the heavens).

Regardless of where it goes, the snake always represents the relationship between continuity and transformation. Considering where the snake is headed adds another layer of symbolic meaning. If the snake is headed down a bad path, then it will continuously “descend” with each subsequent transformation. The bad way of living makes the snake sicker and sicker — each new skin is worse than before. It needs to be set straight to get better, it needs a structure for “ascension.” A rod pointed upward toward the sky represents this. By conforming with the structure, the snake is set straight, healed, corrected, and aimed “upward” toward what is higher and better. This process is discipline. Those who conform with an existential structure throughout the changing phases of their lives are disciples.

The story of Moses and the fiery snakes is that of lost faith, chaos, and discipline. A snake that is on fire burns through its current skin and then burns deeper until it eventually dies. The Israelites’ plan to follow Moses defined their current phase of life. Like how the fire burned away the snake’s current skin, the doubt destroyed the Israelites’ faith in their current plan (a temporary existential structure). The doubt grew and eventually threatened to destroy their faith in God generally. To the Biblical authors, losing faith in God meant spiritual death. A fiery serpent is to doubt as a serpent unmoored from all structure is to evil. (Satan is Biblically represented as an undisciplined snake – nature in pure chaos.)

Through God’s wisdom, Moses reminded the Israelites about the healing power of corrective conformity with the symbolic snake pole. The pole symbolizes how discipline enables ascension — how it can afford progressively better ways of living. Israelites who “looked at” the pole, or who were deeply reminded of the power of discipline, were brought back from the brink of faithlessness (death). It encouraged them to conform with God’s will and trudge onward through life’s wilderness with the faith that they would arrive somewhere better in due time.

This is the context for John 3:16. “Lifting up,” or “believing in,” Jesus/God is like upholding the power of Christian discipline when you are suffering in the life. If you continue to discipline yourself according to the Christian existential structure throughout life’s phases like a snake disciplined by a rod, then you are a Christian disciple who “lives eternally.”

A Psychology

What is the qualitative difference between a life that is disciplined and a life that is undisciplined? How could such a difference be articulated in a general way? These are important but difficult questions.

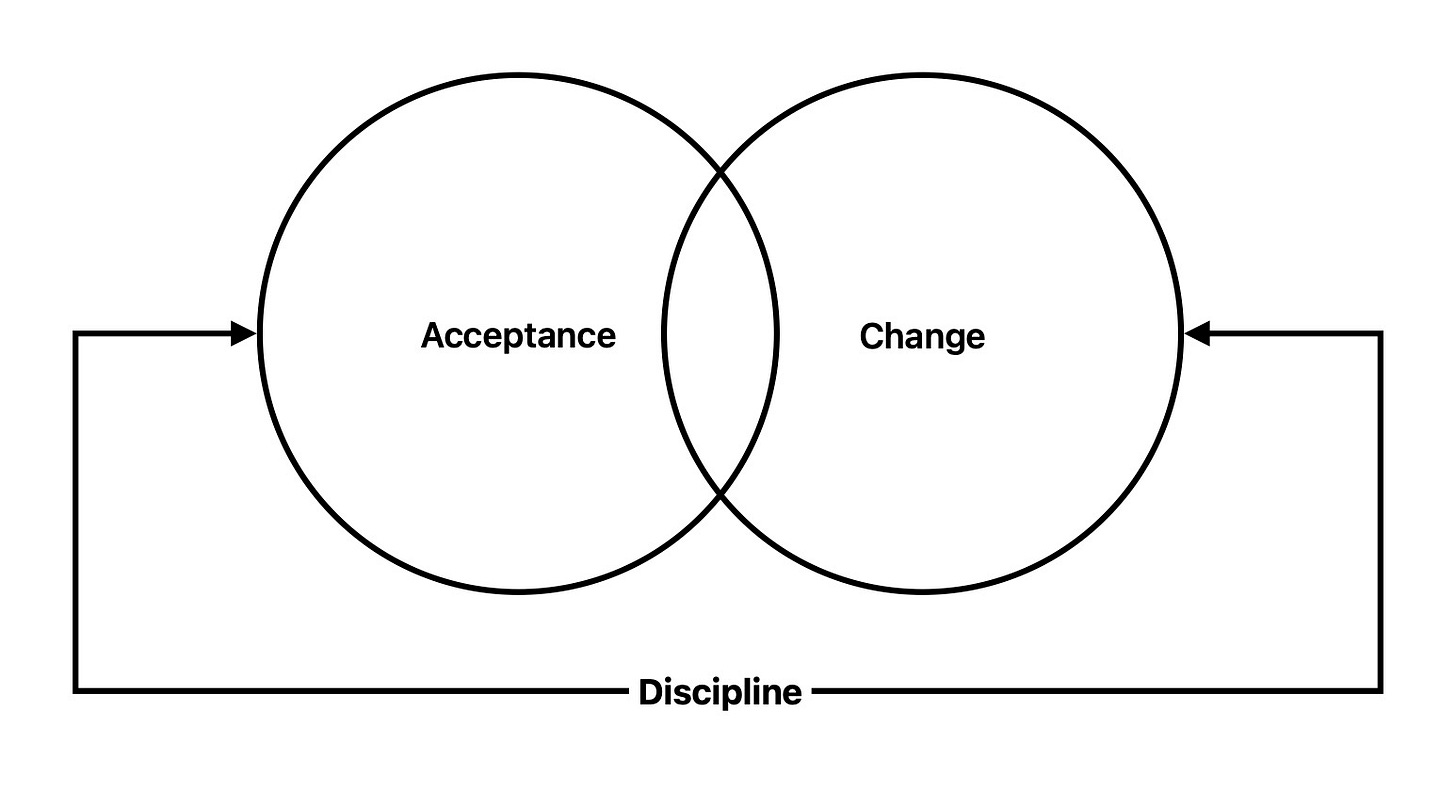

In my view, the key difference is in the degree of integration among the various aspects of living — feeling, thinking, and behaving. Discipline affords existential integration. There are many ways to talk about discipline’s relationship with integrity. I will discuss the dynamic as it pertains to shame.

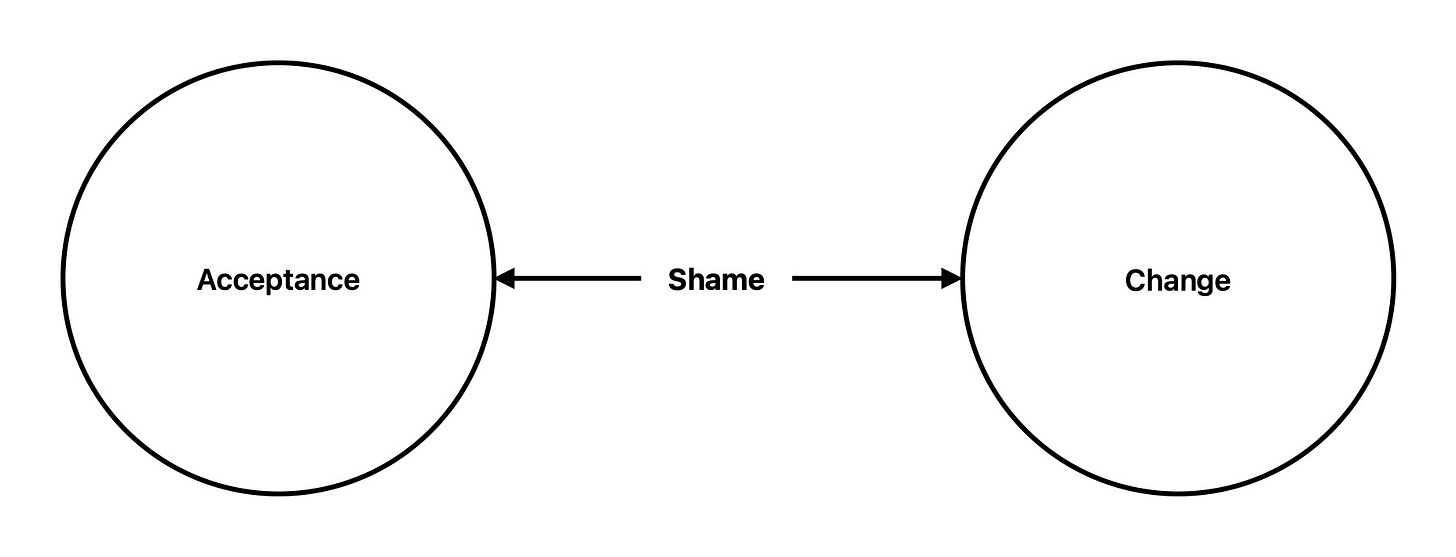

Discipline affords integrity by protecting against the disintegrating effects of shame. Shame is guilt about being who you are currently. Although it can be useful in some situations, shame is by far the most dangerous emotion. Many mental disorders and physical problems result from the damaging effects of chronic shame, or mortification.

I am in a psychotherapeutic program called Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT). It is a type of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) that emphasizes emotion regulation skills. One of DBT’s primary dialectics, or active tensions, is that of acceptance and change. To heal psychologically, one must move through the tension between “I am enough” and “I need to change.”

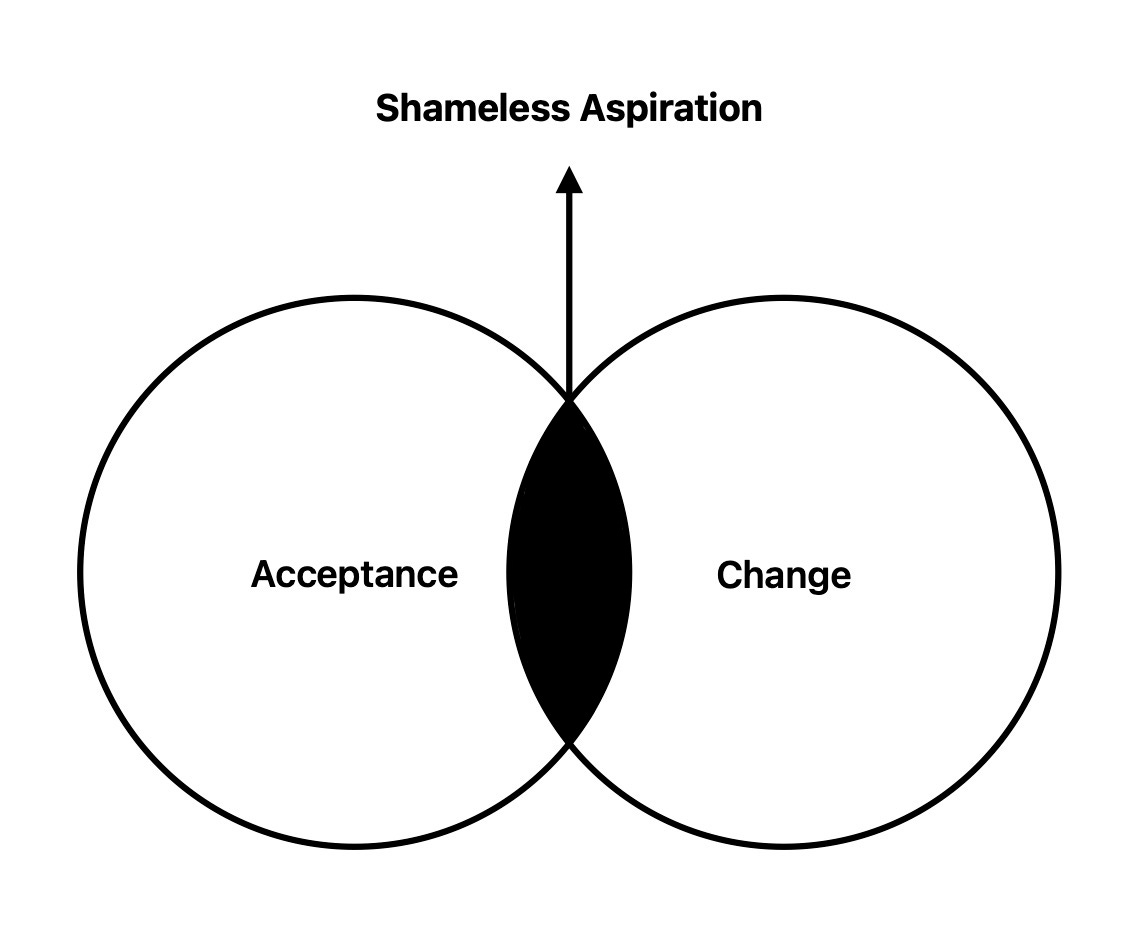

Logically, these ideas contradict. However, the goal is not to somehow hold a logical paradox in mind, but to reach the powerful emotional state of shameless aspiration. Aspiration entails an implicit recognition of limitation. For me to aspire to be like you, I must recognize that you have something desirable that I lack.

Aspiration does little good if it is weighed down by shame. Shame motivates self-avoidance. The ashamed compulsively take drugs, drink, plunge themselves into work, etc. to distract themselves from themselves. Distraction obstructs progress toward aspirational goals by diverting energy away from productive action and toward temporary, and usually harmful, forms of relief. It also diminishes the capacity for aspiration in the first place by creating a vicious cycle of self-loathing and compulsive self-forgetting. It is hard to identify what you want to become when you are stuck in a fog.

Shameless aspiration is a place in which you deeply accept where you are while also wanting to get somewhere better. It isn’t prideful or anxious, but vulnerable and hopeful.

Discipline helps you move through the acceptance-change dialectic and become more integrated in your thoughts, feelings, and actions. Overcoming shame in a sustainable way is a skill that you must practice to learn. You must learn how to recognize shameful thoughts, how to productively interrupt shame spirals, and how to learn applicable lessons from the shame spirals that you failed to prevent or thwart. These tactics aren’t taught in school, they must be learned elsewhere.

Discipline affords psychic integration because conformity with a psychotherapeutic structure like DBT cultivates the powerful emotion of shameless aspiration. In other words, practicing emotion regulation skills with discipline teaches you how to live with greater integrity. The undisciplined person experiences much more shame, and many more conflicts with themselves, than the disciple. Shame and self-conflicts significantly impact the ability to think clearly, live intentionally, form lasting relationships, progress in your career, appreciate beauty, and much more.

A Psycho-Theology

Discipline does not exist on its own, it is a word describing a relationship of conformity between chaotic nature (snake, tree, you) and a specific existential structure (way of life). Disciples in the abstract do not actually exist, only those who work to progressively conform with a specific way of life exist as disciples.

In this case, the psychology provides an abstract dialectical model of the self. It helps explain why and how discipline integrates the self. Through theoretical development and research, DBT psychologists have created useful emotion regulation skills. The psychology helps one skillfully overcome the fundamental existential problem that gives rise to mental illness and spiritual disconnection. However, DBT does not provide a clear existential path for what to do or who to aspire to become. What is the purpose of being psychically healthy?

That is where the theology enters the picture. The theology provides existential priorities and goals. It cultivates structured commitments to family, community, and nature. It organizes people’s activities around common goals and imbues purpose into existence. The Christian theology discussed above emphasizes religious conformity with Biblical ideals and priorities. To discover what these priorities are for one’s specific life, one must personally practice the religious skills in the Christian tradition regularly and especially when life gets hard.

The psychology can be leveraged to explain the practical profundity of ideas in the theology. For example, the phrase “I am a sinner” in Christian theology is powerful because it is an expression of the DBT acceptance-change dialectic. It is transformational for the same psychological reasons that saying “I am an addict” is so important for new AA and NA members. Saying “I am a sinner” in the face of others’ potential judgment involves both radical acceptance of one’s limitations and the recognition of the need for change. It is difficult to say because integrating these apparently contradictory ideas is difficult to do.

Right now, there is no other way for you to be other than how you are. Even if the being that is you should transform, it cannot transform into something better unless you understand yourself intellectually and emotionally. This understanding must include the ways in which you are limited, fallible, and imperfect. You must accept that you are less than your aspiration in order to become more like it. The term “sinner” denotes limitation and the need for change, for the sinner who recognizes sin for what it is (missing the aspired mark) seeks to overcome his sin.

Conclusion

There is so much more that I could say here, and many ways I could further flesh out the theology, psychology, and psycho-theology that I present above. I hope that what is there is sufficient to give a glimpse into the power of psycho-theology. Psychology and theology need not be independent of each other. We would all be better off if they were integrated for they mutually support each other and us.

Psychology is not morally neutral. Cultures war over definitions of “psychological health” and psychotherapeutic approaches. These same cultures disagree about moral values, priorities, and goals. Disagreements about psychology are disagreements about morality.

In my ideal pluralist society, each culture has its own psycho-theology. Each has a vocabulary for discussing mental illness and psychic dynamics in a way that complements its theology, or moral philosophy. I believe integrating the two will help solve our society’s growing mental health problem, which is a burgeoning spiritual crisis.